![]()

This essay was originally published in Re:Search (Krakow: Foundation for Visual Arts, 2014).

In 2014, Aaron Schuman was invited to be the Chief Curator of Krakow Photomonth 2014.

(15th May - 15th June 2014)

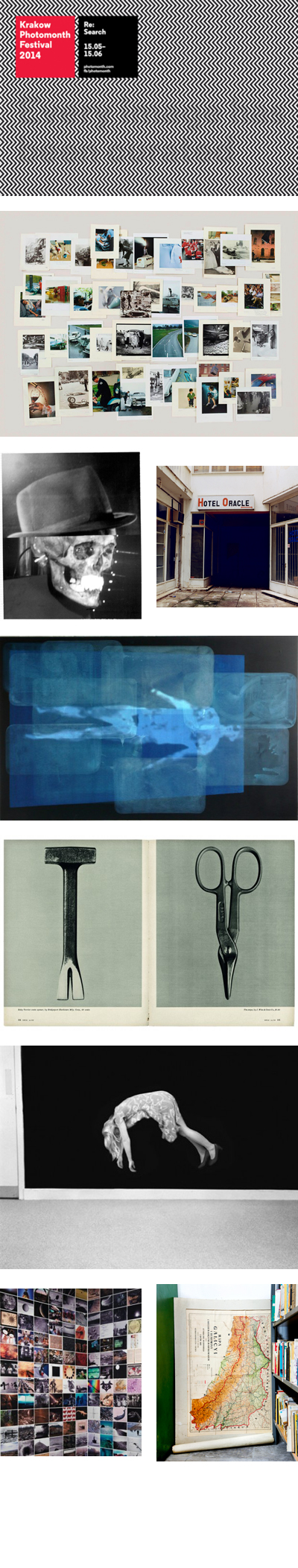

Entitled Re:Search, the Main Programme includes nine exhibitions:

- Taryn Simon: The Picture Collection

- Jason Fulford: Hotel Oracle

- Trevor Paglen: The Last Pictures

- Clare Strand: Further Reading

- David Campany: Walker Evans - The Magazine Work

- Jakub Woynarowski: Echoes

- Aaron Schuman: FOLK - A Personal Ethnography

- Wojciech Nowicki: Radiation

- Thomas Keenan & Eyal Weizman: Forensic Aesthetics

Last year, whilst wandering through the crooked and cobbled streets of Beaune, a small city in central Burgundy, I stumbled upon a leafy square and rather imposing statue dedicated to Étienne-Jules Marey. With antiquated images of lunging fencers, flapping birds, and flying cats flooding my mind, I immediately recognized this name—Marey—from the history of photography. But I was surprised to learn from an impressive inscription carved into the side of the stone monument that Marey was celebrated as a hero by his home town, and considered worthy of such a statue, not simply because of his contributions to the photographic medium. It stated that, during his lifetime, Marey had served as a "Commander of the Legion of Honor, Member of the Academy of Sciences, Member of the Academy of Medicine, Professor of the Collège de France, Creator of the Graphic Method, Inventor of Chronophotography and Cinematography, and Author of the Theory of Movement of Animals and Bird Flight."

In the subsequent weeks, I began to reflect upon how so many of the founders of photography were not so much aesthetes in search of a new and expressive artistic medium, but were instead ambitious scientists, researchers, scholars, and polymaths in search of a visual tool that might serve, support, and substantiate their research - and their search for knowledge - within a broad spectrum of disciplines. I considered how William Henry Fox Talbot was not only an inventor of several of the earliest photographic processes, but was also a chemist, a classicist, an etymologist, an archeologist, and a Member of Parliament; how Nicéphore Niépce was not only Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre's partner in the discovery of the daguerreotype, but was also a soldier, a government administrator, a scientist, a farmer, and an engineer; how Charles Dodgson (a.k.a. Lewis Carroll) was not only a prolific Victorian photographer, but was also an author, an inventor, a philosopher, a logician, an Anglican deacon, and a lecturer in mathematics at the University of Oxford; and so on. And I was reminded that photography was a medium born from empirical curiosity rather than artistic ambition.

In fact, even in its earliest years, photography was often chastised for presuming that it might contain any meaningful creative potential or independent expressive merit in its own right, and was constantly reminded of its subservience to other fields. As the poet and critic Charles Baudelaire wrote in 1859, only two decades into the medium's existence:

"If photography is allowed to supplement art in some of its functions, it will soon have supplanted or corrupted it altogether ... It is time, then, for it to return to its true duty, which is to be the servant of the sciences and arts—but the very humble servant… [I]n short, let it be the secretary and clerk of whoever needs an absolute factual exactitude in his profession—up to that point nothing could be better."

Today, of course - because our use, dependence upon, and understanding of photography has grown exponentially more intimate and more complex throughout the course of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries - Baudelaire's premonition has in many ways come true; photography has in fact "supplanted or corrupted" art (amongst many other things) altogether. Furthermore, we now recognize that "absolute factual exactitude" is not the definition, strength, nor even the purpose of photography - that in truth, this medium resides within a rather murky and convoluted grey area between fact and fiction, the evidential and the personal, the objective and the subjective, the empirical and the lyrical, etc. Nevertheless, as many of photography's most exciting contemporary practitioners and scholars have recognized, despite its inherent uncertainty, such territory is still remarkably rich, and bears incredible potential to be both fruitful and insightful not only in general aesthetic and artistic terms, but also specifically in terms of knowledge and the search for it. In a remarkable turn of events, photography no longer serves as "secretary," "clerk," or "humble servant" to the arts and sciences—in fact, today, it could be argued that the reverse is often the case.

As defined by the Oxford English Dictionary, research—originally from the 16thC. French re-cerchier, "to search with intense force"—encompasses:

• the act of searching (closely or carefully);

• inquiry into things, or pursuit of a subject;

• a course of critical or scientific inquiry;

• a devotion to scientific or literary research;

• a second or repeated search;

• to search into (a matter or subject);

• to investigate or study closely;

And in a number of fascinating ways, such definitions could also be applied directly to the best of contemporary photographic practice, and critique, now taking place. With this in mind, Krakow Photomonth 2014 and this accompanying publication, entitled Re:Search, aim to explore how a number of contemporary artists, photographers, curators, academics, writers, and historians—all polymaths in their own right—engage in research, and use photography itself as a primary starting point for such searches within a broad spectrum of artistic and scientific disciplines, as well as how they employ, incorporate, and manipulate the intricate visual language of this distinct medium in order to embody, express, and critique such knowledge. Ultimately, Re:Search is an investigation into the important role that photography often plays within contemporary searches for and definitions of knowledge, as well as a celebration of photography itself, as an exceptionally unique and exciting form of study, inquiry, investigation, intensive searching - and research - in its own right.

- Aaron Schuman

SEESAW MAGAZINE: "Re:Search" @ Krakow Photomonth 2014",, by Aaron Schuman

Copyright © Aaron Schuman / SeeSaw Productions, 2013. All Rights

Reserved.

This site and all of its contents may not be reproduced, in whole or

in part, in any form, without the written permission

of Aaron Schuman, and other additional artists involved in the production

of specific works exhibited on this site.