![]()

This interview was originally published in the British Journal of Photography (2008).

TOD PAPAGEORGE began to photograph in 1962, during his last year at university. Over the course of the 1960s, he became closely associated with the street-photography movement in New York, befriending and collaborating with notables such as Garry Winogrand, Joel Meyerowitz and John Szarkowski, then the Director of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art. In both 1970 and 1977 he received Guggenheim fellowships to pursue his photographic work, the results of which have recently been published as American Sports, 1970: Or How We Spent the War in Vietnam (Aperture, 2008) and Passing Through Eden (Steidl, 2008), which was recently shortlisted for the 2009 Deutsche Börse Prize. Since 1979, Papageorge has been the Walker Evans Professor and Director of Graduate Studies in Photography at the Yale University School of Art.

AS: Aaron Schuman

TP: Tod Papageorge

AS: You’ve often said that you were originally inspired to pursue photography because of Henri Cartier-Bresson. Where did you find his work in the first place?

TP: It was totally by accident. I was taking an introductory photography class at university, and I guess I was curious enough to go to the library and look at some bound periodicals. And there was this photograph by this man I’d never heard of; it was totally shocking to me. It provoked me to literally do everything I could in that library to find any other pictures by him. I think I found one more. But those two pictures inspired me to become a photographer.

AS: Had you taken photography seriously before that moment?

TP: No, but I had this itch to take a photography class. It was my last semester, I was majoring in English and writing poetry, and I very much wanted to take this class. So something was moving me, but I don’t know what it was. The charming end to that chapter is that I won the school’s poetry prize – fifteen dollars – and with that I went to the university bookstore and ordered an out-of-print copy of The Decisive Moment.

AS: Was there a definitive point when you swapped poetry for photography?

TP: I think it was then. I recognized in photography a way of making poetry without the terrible agony of putting words together, thinking in my delusion that photography would be easier, and never suspecting that it was harder, or at least as difficult.

AS: You then travelled to France and Spain.

TP: Well first I spent a year in San Francisco, where I saw Robert Frank’s work and Walker Evans’s work, although it was because I saw Frank’s work that I looked for Evans. I was completely confused by American Photographs; I didn’t really get it.

AS: I don’t think that many people do the first time around.

TP: Well John Szarkowski didn’t, although Garry Winogrand did. Very interesting. So first there was that year in San Francisco, then a year in Boston, where I saved every penny and then went to Europe. I lived in Spain for six months, and in Paris for three months.

AS: Did you go to those two places because of Cartier-Bresson.

TP: I do think so. But also, in college I had an art history teacher named John O’Reilly, who was an artist and a very inspiring teacher. After I took that art history course with him, he quit university teaching and went to live in Spain. We had a correspondence during the year that he was there, and he just loved it so much. Then a year or two after that, I saw the Cartier-Bresson pictures. I must have also seen a few of Robert Frank’s pictures from Spain, so all arrows were pointing to Malaga.

AS: And then Paris?

TP: Yes, when I lived in Paris I went to the cinematheque everyday. I love film, and at that point I believed that I wanted to be a filmmaker. At the American Center there was this help-wanted ad up on the wall: ‘Help French Film Director With His English’. Can you imagine! I got the job, and he was this great guy – at one point he asked me if I would be his Assistant Director if the film that he was hoping to do came through. But I was there on the morning he called the producer in Hollywood, and the whole thing fell apart; it was just awful. In any case, I left Paris thinking that I wanted to be a filmmaker. Then in New York, I met Robert Frank. He was working on Me and My Brother, and he asked me if I’d be willing to be a grip, so everything was great. At the same time, I met Garry Winogrand. I ran into him on the street a few times, and eventually he invited me to his apartment. So I knocked at the door, and he said, ‘Where are your pictures? You didn’t bring photographs? Who wouldn’t bring me pictures?’ Anyway, we had a great night, he showed me stacks and stacks of pictures – a lot of it was what became 1964 – but it didn’t tell me I could be a photographer. It told me that America could still be photographed – that Robert Frank hadn’t done everything.

AS: So when you first returned to America, you had doubts about taking photographs there?

TP: When I was first in New York, I felt very strongly that it was impossible to photograph it. The complexity of the city – the visual field – it was all just too immense.

AS: So it wasn’t a ‘kid in a candy-store’ scenario?

TP: No, not at all.

AS: Because from Winogrand’s pictures you get the sense he had that ‘kid in a candy-store’ mentality.

TP: Oh, definitely. I remember saying to him once, ‘Don’t you ever miss nature?’ And he looked at me and said, ‘Well, I guess the city is my nature.’

AS: Did you spend a lot of time watching Garry work, trying to learn how he photographed?

TP: This is one of the interesting things to me about my Spanish pictures. It’s embarrassing to say, but I was just very gifted as a photographer. Just recently I scanned them for the first time, and to see the pictures that I took without even knowing the name, Garry Winogrand, is pretty interesting. You know, I took this workshop with Garry in his apartment - he let me in for free, and Joel [Meyerowitz] was there as well.

AS: Anyone else?

TP: Joel’s wife, Vivian. And Garry’s girlfriend, Judy, who became his second wife. And there was one due-paying copywriter from advertising – a very serious, very nice guy – but he was probably the only person paying money. In any case, Garry loved it. We drank cup after cup of coffee, and he was working out what he thought about photography. Looking back on it, it really was a remarkable period. He was totally Socratic. He just couldn’t understand something unless he asked the question and you tried to answer it.

AS: Almost like he photographs.

TP: Exactly. A lot of it was what Socrates said: ‘I don’t understand anything.’ He really couldn’t understand something until someone tried to explain it to him. I always say that I learned how to think from him. At the end of that first class that Garry held, I was the last person to show pictures. Garry looked at them and said, ‘These are crying to be published.’ He was very serious about photography, so that meant a huge amount to me. That was vindication, because by then I’d followed this dream for four years without showing anybody anything, so it was a great moment.

AS: Is that when you realized that photography was something you could actually do seriously for the rest of your life?

TP: No, inwardly I’m a very sure person. But Garry’s photography dumbfounded me. I just couldn’t believe how great it was, and that he’d done the 1964 work in four months was just unbelievable.

AS: Was Garry competitive in any way?

TP: No, he was the most profoundly uncompetitive person. It’s just remarkable. For him it was all about photography – totally pure. He had very strong opinions about other photographers, but never to the point of putting himself above anybody else.

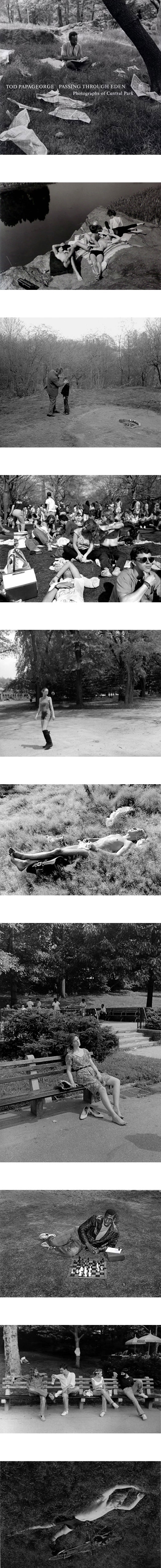

AS: Tell me about the project, Passing Through Eden.

TP: Well, it wasn’t a project. The earliest pictures are from when I first got to New York. Then in ‘77 I received a second Guggenheim Fellowship, so I had time and money to devote to something. And since I was walking through Central Park every day on my way to MoMA – to work on Garry’s ‘Public Relations’ – I thought, ‘Why not the park?’ It really wasn’t any more formed than that; it was just something I kept returning to.

AS: So what was the impetus for publishing the work now?

TP: Last year I got an email from Paul Graham asking me various questions about 1970s American photography, because Michael Mack and he were thinking about doing a book with Steidl. I answered rather exhaustively, and sent Paul some pictures of my work. That’s what started the ball rolling. Paul was extremely supportive all the way, although he had a very different idea about it - as you’d expect, it was much more conceptual - but I wanted to make something much more Chaucerian, much more varied.

AS: You mention Chaucer, and there certainly is a sense of mystery or danger in many of the photographs. There’s a sort of menacing atmosphere: ‘Do you dare go in the woods?’

TP: Yeah, ‘Sunday in the Park with Papageorge’!

AS: As you explain in the accompanying essay, the book’s sequence and structure are inspired by the Book of Genesis. How did that theme first reveal itself?

TP: Michael Mack said, ‘These little pictures of nature are very good. Maybe you should think about adding a few more.’ So I started to think about how I could do that, and how I would sequence it. For some reason I started with the Creation, but it was totally mad idea. It took a long time for it to make any sense at all, and I’m sure that it makes much more sense to me than anyone else. But it allowed me a certain freedom in organizing the book. There’s a kind of darkness in the beginning, which is undeniable whether you know the analogy or not. For me, one of the great streams in the history of photography is the so-called ‘narrative’ stream, and it was very important to me to reinforce the sense of that. It’s not a good word, ‘narrative’; it’s not the best word, but I don’t know what the best word would be. In any case, it’s very important in terms of the way I read and see photographs. Photography is not a simple illustration, and maybe the most important thing is that it forces an intelligent viewer to think about the relationship of the photograph to so-called ‘reality’ or ‘truth’. If you’re reading a photograph as a tale, then what does that have to do with whatever was out there in the world? It’s this transformed thing. And that’s always been my obsession while teaching at Yale as well, so I’ve had students like Gregory Crewdson and have been an effective teacher, because I was certainly never talking about photography as a deliverer of the ‘truth’. It’s all fiction to me, whether it’s a complex one or an illustrational one.

AS: Was that something you learned from Garry?

TP: I knew it from that first Cartier-Bresson I saw. That’s why it was so powerful to me – because I knew that it was another world; the photograph. It was completely different, and that’s why it was so powerful.

AS: In Mirrors and Windows, John Szarkowski wrote, ‘One of the by-products of photographic education has been the creation of an appreciative audience for the work of the student body’s most talented teachers.’ What inspired you to start teaching?

TP: I needed to survive. Robert Frank introduced me to his close friend, Marvin Israel, who was Diane Arbus’s lover. Marvin was also the art director of Harper’s Bazaar, was a very powerful figure in that fashion world, and was also a painter and a very serious artist. Anyway, Marvin taught a photography course at the Parsons School of Design, in the fashion illustration department. He wanted to stop, so he asked me if I would be interested in taking over – that’s how it started.

AS: Did teaching come naturally to you?

TP: I’d probably be embarrassed to hear what I was saying then, but I guess I had a strong effect on the students. I was very intense. So yes, it came naturally.

AS: Did you find it fulfilling?

TP: It’s not as if I would walk away from a class feeling exhausted, or angry, or saying, ‘What a way to make a living!’ Never. I’ve taught all kinds of students, and a lot of them have become well-known photographers, even back then. The year after I started at Parsons I also taught at Cooper Union – Mitch Epstein was a student, and Len Jenshel; lots of different people. The whole thing about professing is, if you have someone that’s passionate and can be articulate about the subject, it works. I mean, I can give a Brassai lecture – or a Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank, or Winogrand lecture – and I know that no other person in the world could give a lecture remotely like I can, because of the way that I understand their work and what I can articulate about it. But that’s at the end of many years of teaching along with a lot of experience, so it’s a very special thing.

AS: Every ten years or so, you hear that there’s about to be a ‘resurgence’ of street-photography. Is it something that can really be ‘resurged’?

TP: I don’t think so.

AS: Because Frank took Evans’s ball and ran with it; Winogrand took Frank’s; and so on. Do you see anyone in more contemporary terms that has taken inspiration from 1960s street-photography and made something of their own with it?

TP: The person who has come closest is Philip-Lorca Dicorcia, with his ‘Streetwork’. I think it’s very good work. I’m not sure if it’s great work, but it’s very, very good. In other words, I think that he did take it someplace else. But since then, I don’t know. The street has changed since then; it’s so different. It seems like it was a grittier world back then or something.

AS: When I look at your generation’s pictures, I see a New York that hasn’t been gentrified. Nowadays, it’s hard to take a picture on the street without a Gap or a Starbucks in the background.

TP: Exactly. And when you take it in color – which you almost have to do today – those signs and words have a totally different presence that they would in a black-and-white picture.

AS: Do you think that this sense of history or nostalgia heightens your pictures - and the work of your contemporaries - in the eyes of the contemporary viewer?

TP: I don’t see it. I look at these photographs and it feels like I took them yesterday, so I don’t read them that way at all. But I guess I can understand how one might.

AS: Because for people of my generation, that New York never existed in our lifetime – it’s a different world. It’s not difficult for me to look at Passing Through Eden and understand it as a fiction or narrative tale, because it’s a world that never existed for me.

TP: Whereas I can look at Garry’s pictures – even from ’64 – and they look utterly contemporary to me. I guess I want to deny the actual reality of the world today. Another thing is the relationship of the photographer to the social world. It’s unusual for today’s photographers to look beyond themselves or their own studios. But isn’t that one of the great strengths of the medium? As Garry would always say, ‘Who could imagine what appears in photographs?’ The power of the imagination is very limited - with most of Garry’s or my pictures, you could never imagine them.

AS: You couldn’t construct them.

TP: Exactly. You couldn’t imagine it to construct it. So instead, photographers have someone staring up at a ray of light, and that’s supposed to substitute experience.

AS: With that in mind, why do so many of your most famous students attempt to make constructed images?

TP: I don’t think that it’s my responsibility to tell my students what to do. And as I said, my general approach is to talk about photography as a fiction-making medium.

AS: What do you honestly think of the state of contemporary photography?

TP: What do you think I think? Ultimately, I think that you have to have a vision of the world. I don’t feel hopeless about it; Philip-Lorca Dicorcia is a significant figure.

AS: It seems like a lot of contemporary photography is about photography, more than anything else.

TP: Yes, but in a sense, no one’s work is more about photography than Garry Winogrand – it’s just that he had a very interesting view of photography, which was incredibly complex. I do talk to the students at Yale about using a small camera more and more. Taking so many pictures taught me a lot, even unconsciously, about being out in the world and using a camera to make pictures. It also taught me a lot about different picture forms, and the use of space. Many students today are completely ignorant about that, so the pictures are generally something plopped in the center of the frame and digitally printed to 40x50. I shouldn’t castigate the students, but it turns up in the galleries too, and it’s just not very interesting; it’s not very satisfying as a visual experience. Maybe it’s simply a case of finding a number if interestingly tormented people. Garry Winogrand, Robert Frank, Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander - they were all lunatics.

SEESAW MAGAZINE: "Park Life - An Interview with Tod Papageorge", by Aaron Schuman

Copyright © Aaron Schuman / SeeSaw Productions, 2007. All Rights

Reserved.

This site and all of its contents may not be reproduced, in whole or

in part, in any form, without the written permission

of Aaron Schuman, and other additional artists involved in the production

of specific works exhibited on this site.