![]()

(This interview was originally conducted for an article published in Dazed & Confused;

in conjunction with The Photographers' Gallery and the Deutsche Borse Photography Prize 2011.)

AS: Aaron Schuman

JG: Jim Goldberg

AS: How did you first get involved with making work about people who are marginalised or on the edges of society?

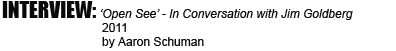

JG: I’ve always been interested in perceptions and creations of the ‘other’, maybe because I felt that way as a teenager. I first began working with displaced or forgotten people – people on the edge – during Rich and Poor, which I started 1977. My understanding of outsider situations then grew with the projects that followed: Raised by Wolves, Nursing Home and Race. So it was natural that I felt a gravitational pull towards issues of displacement in Europe. I had a sense that the refugee, immigrant and trafficked people’s stories were not being told, and that their perceptions were not being observed and considered.

AS: How does that factor into the idea of you as a photographer? Considering the ways in which you incorporate text and involve your subjects in the images themselves, you’re obviously aware of notion that the photographer could easily be seen as speaking for the subject, and highlighting their ‘otherness’ – in a sense, distancing them even further from the viewer. So I’m curious how you first came to the realisation that maybe you could incorporate text or markings by the subjects themselves.

JG: I think that, with all my projects, I’m kind of obsessed with this idea of total documentation, which started out with when I began integrating my subjects’ writing on the images – which first happened in Rich and Poor. And then I enlarged it by having black and white images with text, and then including colour, video, then audio and then ephemera and using installation – especially in Raised by Wolves. That said, I think that it’s just been the way that I’ve always worked. I’ve always approached my projects using a variety of mediums, and I try to use them with some purpose.

AS: What purpose does the photograph serve in that respect? And what do you feel your role is as the photographer?

JG: Being a photographer is where I started, and it’s mutated from there. The photograph is kind of a proof – a proof that I actually met these people, that they actually have lives, and that they’re worth considering. When I take a photograph, I use film and I make contacts in order to look at them – ‘proofs’. And it’s a really interesting play on the word – the image is proof. You know what I mean?

AS: Yes, absolutely; that makes perfect sense. The photograph acts as a kind of evidence as much as anything else, or at least a part of the evidence.

JG: It’s a part of the evidence. I’m not saying it’s the truth – it’s part of the evidence.

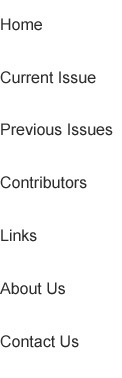

AS: I wanted to ask you about your process by looking at one particular example: ‘GREECE. Athens. 2003. Muzaffar “Alex” Jafari writes about his journey on foot from Afghanistan to Greece via Iran. Now Alex is in school and supports himself by working in a call center.’ (Courtesy of Jim Goldberg / Magnum Photos). What’s the story behind this image?

JG: I met Muzaffar in Athens, early on in the Open See project. He worked in a calling centre, so I would visit him at his job. I could sort of tell you what the text means. Literally, it’s his story about walking, travelling from Afghanistan to Greece – that’s written on the outside. On the inside, written in his shirt, it’s about what he does in Greece, and how he really wants to be in education. He’s a really smart guy. He comes from a pretty well-off family, but if he had stayed at home he would have been killed. I believe that everyone has more than one life story, depending on who’s telling it, and where that person stands. So it’s not only about what he thinks, but it’s also about the audience and how they take it. So the interaction between the subject and viewer is really personal. Usually my goal is to frame that conversation as a thoughtful almost encounter, rather than a knee-jerk reaction like ‘Help me, help me, I’m a poor immigrant’.

AS: And how did you first meet Muzaffar?

JG: I really don’t remember; I remember where he worked. I kept in touch with him for years, but I haven’t heard from him in a while. I don’t know where he is now. I try to stay in touch. Actually, I’m going to look for him, because now that we’re speaking it makes me want to write to him again.

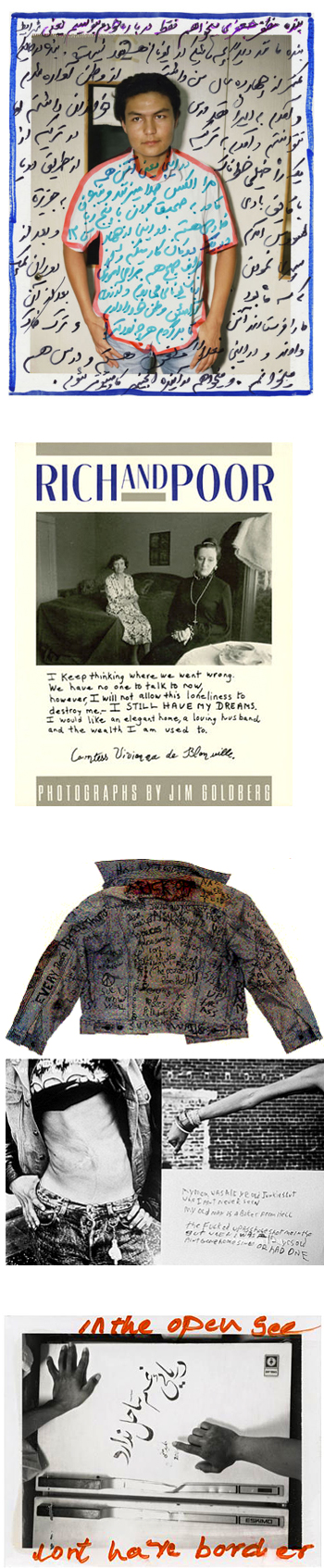

AS: How did your project, ‘Open See’, begin?

JG: It began as a Magnum commission. Basically, it started off as a project about immigrant culture in Greece, and was intended to be shown in Athens, as part of the opening of Olympic Games in 2004. Then it blossomed into a full-blown personal project. Part of the reason I joined Magnum was because I didn’t want to be limited to the confines of the art world, so it seemed like an exciting way for me to disseminate my images; you know off the gallery wall from the gallery wall. Also, this was my first time creating a body of work outside of my own country, and a whole new learning curve was built into that experience.

AS: When you exhibit these works, do you always provide translations? In the case of the image of Muzaffar, unless you speak Farsi, it’s difficult to interpret.

JG: I understand that it’s tricky. Visually it is beautiful, so in some ways you could just look at it and experience it almost like an Indian miniature. But I do have a lot of translations when these works are shown – I would say half of the images that I show, maybe more than half, have translations. In some ways I don’t want to give it all away; I don’t want to tell it all. And who are we, as Westerners, to expect to have translations always done for us? Sometimes I think it’s okay not to be told everything, to not have the answers to everything. There’s sometimes a reason not to give all the answers. So I don’t know if I’m so much telling stories as witnessing personal histories as they unfold. I’m in a unique position of relating a story as it unfolds, and at the same time I like to acknowledge the multitude of ways in which it can be told, in a Rashamon kind of way. The multi-layered quality of life – of people’s motives and actions – is what fascinates me, rather than having answers.

AS: Has ‘Open See’ changed the way that you work, or has it influenced what you hope to do next?

JG: Well it hasn’t changed my work, but my experiences have changed. Before this project I would go out of my front door and what was in front of me was what I documented. With ‘Open See’, I had to travel, and the people I was working with didn’t really have the luxury of time or freedom, so I couldn’t really go back and find them easily again. So in that sense, it changed the way that I worked. In a way, these people were in a state of constant flux. It’s a fragile existence.

SEESAW MAGAZINE: '"Open See" - In Conversation with Jim Goldberg', by Aaron Schuman

Copyright © Aaron Schuman / SeeSaw Productions, 2011. All Rights

Reserved.

This site and all of its contents may not be reproduced, in whole or

in part, in any form, without the written permission

of Aaron Schuman, and other additional artists involved in the production

of specific works exhibited on this site.