![]()

ADAM BROOMBERG and OLIVER CHANARIN are a photographic team based in London. Together they have produced five photographic books; Trust (2000) which accompanied their solo-show at The Hasselbad Center; Ghetto (2003) a collection of their work as editors and principal photographers of Colors magazine; Mr. Mkhize’s Portrait (2004) which documented South Africa ten years after apartheid and accompanied their solo-show at The Photographer's Gallery; Chicago (2006), an exploration of contemporary Israel, published by SteidlMACK in conjunction with a solo-show at The Stedelijk Museum; and Fig.,published by SteidlPHOTOWORKS in 2007 with an exhibition at The John Hansard Gallery, UK. Broomberg and Chanarin regularly teach workshops in photography, as well as lecture on the MA in Documentary Photography at LCC in London. They are the recipients of numerous awards, including the Vic Odden award from the Royal Photographic Society and continue to work for a number of magazines including The Guardian Weekend and The Telegraph Magazine.

For more information, please visit : http://www.choppedliver.info/

AARON SCHUMAN is an American photographer, editor, lecturer and critic based in the United Kingdom. He received a B.F.A. in Photography and History of Art from New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts in 1999, and an M.A. in Humanities and Cultural Studies, from the University of London’s London Consortium in 2003. He has exhibited his photographic work internationally, and has contributed to publications such as Aperture, ArtReview, Modern Painters, Foam, HotShoe, Creative Review, The Face, DayFour, The Guardian, The Observer and The Sunday Times. He is a Senior Lecturer in Photography at the University of Brighton and the Arts Institute at Bournemouth, and is the founder and editor of SeeSaw Magazine.

For more information, please visit : http://www.aaronschuman.com/

This interview was originally published in Hotshoe International (#150 - Oct./Nov. 2007):

http://www.hotshoeinternational.com/

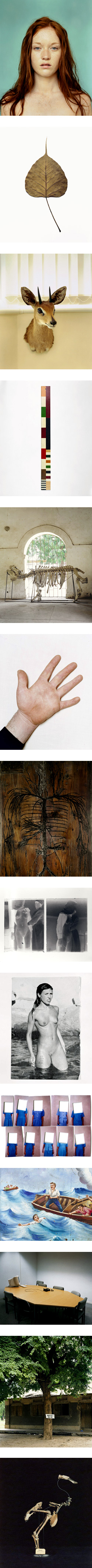

Several years ago, Photoworks commissioned the photographers, Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, to produce a body of work in the southeast of England. After coming to a dead end with a series of cul-de-sacs, the partnership became inspired by the Victorian mania for collecting, evident in museums such as Brighton’s Booth Museum of Natural History, which houses amongst other things a collection of pinups, an osprey egg, the corpse of a merman, and a unicorn’s horn. Noting the parallels between their own work and this obsession for both possessing and exhibiting such curiosities, Broomberg and Chanarin embarked upon the ambitious task of producing a collection of photographs that assumes a similar approach to the contemporary world. The resulting publication, Fig., simultaneously exploits and criticizes the colonial tendencies of Britain - and of the photographic medium itself - offering an challenging, playful and strangely seductive take on the dilemmas facing documentary photography today.

AS – Aaron Schuman

OC – Oliver Chanarin

AB – Adam Broomberg

AS – To begin, what first inspired the concept for Fig.?

OC – Well, there’s something quite strange about being a photographer. You go off, take these pictures, come back, develop the film, then have this set of contact prints that go into a box and then just sit in an archive. Adam and I have always said to each other how pathetic that little bit of plastic negative feels, in relation to the experience of having been there. Also, there’s the strange habit of photographers - almost like collectors - where you’re accumulating all this evidence of your experience in the world.

AB - We read a lot about the psychosis of collecting. Photographers are very strange beings. I think that a lot of photographers suffer from that strange state which makes you think that you’ve got to collect to survive.

OC - So with Fig. we started off by thinking about the act of collecting - or photography as an act of collecting, rather than as a process of making images - and comparing photographers to collectors.

AB – And also, about how collecting is a very colonial experience, and a very colonial practice.

OC – As is photography.

AB – Photography and colonialism grew up at the same time, and sponsored one another. So that’s a very big theme within Fig.. It’s very much a reflection of our experience of documentary photography, but it’s also trying to be critical of the genre, and trying to place it within this colonial history.

AS – But in theory, what you do is very old-fashioned, in the sense that you go off to faraway lands, ‘collect’ obscure people, places and things, and bring them back to show to people in the West. Have you yourselves been criticized for assuming similar colonialist tendencies?

OC – That’s a very good question. This project originally came out of a commission by Photoworks, and the original brief was to make a piece of work in the southeast of England. We spent a year thinking about it, but we’ve never made work about Britain, and our work has often focused on what you might call ‘exotic’, very photogenic subject matter. I think the camera, as a personality in itself, seeks out the outrageous and the extreme. And we have been criticised - and we’ve criticised ourselves - for finding that fascinating.

AB – But to be honest, I don’t think we’ve been given enough criticism. Ollie and I both read this book by Janet Malcolm, The Journalist and the Murderer, and she talks about the fact that when someone meets a journalist they should be most on-guard. But instead, they actually open up and respond to this person as if they were some kind of benefactor, rather than a malevolent figure. We’ve had similar experiences when we’ve done portraits. Firstly, the fact that people agree to be photographed always astounds me. Secondly, it’s such a manipulative process, and because we’ve been in these exotic places, with marginalized people, they’re generally not aware of the power of a picture.

AS – Does your partnership add another dimension or degree to that manipulation?

OC – I think it does, because we’re two different people. We share a lot, but at different moments, we have very different morals. There have been a few times when we’ve confronted each other - when something was very uncomfortable for one of us, and wasn’t for the other. And at that point, we’ve had to say, ‘Do we take this picture and discuss it later, or do we not take the picture?’ That’s been a debate that’s gone on since we started working together.

AS – So do you take the picture?

OC – More often than not, we do. Because I think that sometimes it’s hard to evaluate the morality of a situation in the moment; it’s much easier when you step back. But in the moment, you’ve got to take the picture and you kind of go into automatic; it’s only weeks later, hundreds of kilometres away, that you can sit and really look at the image.

AB – We recently did some work in Ecuador with the artist, Gabriel Orozco, and there was this uncomfortable and quite critical moment when we took one picture. If Ollie and I were alone, we would have quite easily taken that picture because, first of all, we’re so used to that dilemma - being in that very uncomfortable place, but knowing that the final product is going to highlight the situation, and so it’s important to take the picture. But Gabriel got really upset.

OC – Maybe you should explain the scenario, otherwise it’s a bit confusing.

AB – Okay, so the scenario was that we were in the middle of the rainforest, and there are local tribes that have lived there for centuries. But since the oil companies have come in and built their roads, the brothels have come in, the alcohol has come in, the loggers have come in, and these tribal people are left with the choice of either to move, or to get conscripted into the oil companies and become workers in the oil fields. Hence, in a matter of minutes, they lose their culture. We were on an official tour with one of the oil companies, and at the end of tour some of these men came up to us in traditional costume. But they were wearing underwear, and you could see that they were uncomfortable; it was just this corporate theatre show put on for us. We were all aware of it. They were dancing in front of their prefab huts, and Ollie and I walked to the back of the huts and saw all of their Western civilian clothes hanging up. So the whole charade was clear to us. And Ollie and I had a two-second little banter, ‘Should we do it, or should we not?’ And then Ollie said, ‘Lets take them into the jungle. Let’s take this charade to the furthest point, and we can turn the jungle into scenery.’ So it was clear to us; we hardly expressed most of that debate, but we still knew where we were going. But Gabriel and the rest of the team started freaking out. ‘Don’t you realise that these guys are being exploited! You can’t go into the jungle!’, and so on. And we were like, ‘Yes, we know.’ There was this excruciating half-hour while we took the picture, with everyone else really uncomfortable behind us. But in the end, there’s something fascinatingly odd in that picture.

AS – How do you express to the audience that you’re actually documenting the charade, rather than making a charade yourselves?

OC – I think that, if you look into the picture, the clues are all there. And I think that we expect a certain intelligence of the viewer to interpret those things. The picture looks like a nineteenth century ethnographic image…

AB – Apart from their underwear…

OC – But if you look at our picture, their not the kind of people you see in National Geographic.

AS – They’re not ‘noble savages’.

OC – Right, they’re not naked. Actually, they’re ashamed of their nakedness, and they were wearing their underwear. So all that uncomfortableness is in the picture, if you look for it. But at first glance, the picture looks like a picture you’ve seen a million times.

AS – Fig. seems like a project which is focused as much on the dilemmas of photography, collecting, ethnography, museumology, and the exoticization of the world as it is with the subject matter of the photographs themselves. It’s really an exercise in editing and re-contextualization. All of the photographs have a context in themselves - whether its dealing with the Rwandan genocide, or suicide bombs in Israel, etc.- but all of a sudden, by grouping them together and sequencing them in completely different way, they transform into something else as well.

OC – Yes. For example, there’s a set of pictures of flowers taken in Hotel Rwanda, which are quite haunting, and they’re intimated at genocide without actually showing you a picture of a body strewn on the ground covered in lime dust. When we go into these situations, one thing that we always try to do is think of other ways to tell stories and make images. I think our last book, Chicago, is like that, in that we’ve all seen these pictures of Palestine and the conflict, and there’s plenty of cliché images, so we tried to imagine how we could create images that had some kind of surprise effect. I’m not saying that we necessarily succeeded, but as photographers we feel the need to work harder to create new images, even if they’re focusing on an old subject.

AB – And we want to make more intelligent images. With the Rwanda pictures, you look and see cut flowers, and think memorial. But then you think, “Well, cut flowers are an imported, almost colonial practice. We’re in Africa. There’s a genocide that’s very closely related to Europe,’ and so on. All of these things are intrinsic to the work.

AS – Why did you find the prospect of photographing the south of England so difficult? What’s so hard about doing a project at your doorstep, rather than in an ‘exotic’ or distant land?

OC – Yes, it was quite a challenge for us, and we shied away from that challenge by making Fig. about other places. But in the end, it became about this relationship between Britain and it’s empire. And I suppose that’s what resonated with us, because we both live in Britain but we’re not from here, so we are strangers at the same time. Also, there’s something, a kind of humour and culture in Britain, which we just don’t have access to.

AB – We really appreciate it and love it, but we don’t entirely understand it.

OC – One of the first things that we proposed to do was a series of cul-de-sacs around southern England.

AS – And then you shot two and thought, ‘This isn’t going to last.’

OC – Exactly.

AS – Instead, you seem to have adopted very British approach, that colonialist perspective and a mania for collecting.

OC – I suppose the whole language of Fig. is quite British.

AB – Absolutely. The insistence on categorization. The false sense of objectivity.

OC – And the fact is that many of these museums – the Booth Museum and so on – still exist. There’s still that way of thinking in this country.

AS – When you find a subject to photograph, do you feel that you have to exhaust it to no end, or do you know where to stop?

AB – With a lot of projects, we end up shooting enough material for a book in itself. We probably have about three or four hundred pictures from each series.

AS – Exactly. So you also possess this obsession for collecting.

AB – That was a trick question! But yes, I guess that Fig. takes the piss out of that a bit, in that it’s not comprehensive whatsoever. At the most, it’s just three or four pictures from each series.

AS – So one of the faults of Fig. is that it flits arbitrarily from one thing to the other, but in turn, that critiques the whole notion of collecting comprehensively.

AB – And yet, we’ve spent just enough time with each subject to not be able to criticize ourselves.

AS – But if you look at the photographs in Fig. without reading the accompanying texts, the links between them are almost invisible. It seems like Fig. is almost as much an exercise in sequencing and editing both image and text, as it is in making photographs.

OC – Yes, I think that there’s something in Fig. which lets you know that you’re being manipulated. You know that the connections between pictures are almost arbitrary, or are at least very tenuous. But yet they string together a vague narrative, and as a viewer you somehow want to be seduced by it; you allow yourself to be guided through it even though you know that it’s quite tenuous. Somehow you become absorbed by the storytelling.

AB – But Fig. also undermines the empiricism that is embedded in that museum language; you know, ‘This is the truth. We’re going to lead you through it.’ Some of the links are so crazy that you’re taken aback.

OC – I guess there’s something quite naïve about it. Also, there’s an accompanying essay in the book by Julian Stallabrass. He writes about the kinds of texts that you find in these types of books - the kind of ‘art essay’ that is designed to categorize and explain a piece of work, and then insert it into the history or art or photography or whatever. And he says that, if he’s to take the thesis of Fig. seriously, he’s not able to write that type of essay, because he’d basically be doing the exact thing that we’re criticizing. So instead, it’s a self-referential essay about essay writing.

AB – Which very much mirrors the ways in which Fig. is critical of documentary photography. So they sit nicely together.

AS – So much of documentary photography, at least in the twentieth century, has been about capturing a moment or an instant. Being in the right place, at the right time, has often been as important to photographers as how they construct the image. But your work is very different.

AB – Yes, our work is definitely a move away from that. Politically speaking, we often talk about how war photographers are so much a part of the system of conflict, and how the photographers on the frontlines are kind of colluding in that system. So much of that photography - the ‘Baghdad Boys’, and so on - is not challenging the status quo anymore; it’s part of it. And I think that it’s important to make pictures that are challenging. It’s very clear to us that we either have to come either before or after the fact. We consciously avoid that moment of action.

OC – Furthermore, those kinds of images are just replicated on television anyway. They’re totally redundant. Photographs in which the ‘instant’ is visible are as manipulative and as constructed as any other. At least in portraiture the person being photographed has some of control in the process; they’re not being caught completely unaware. And I think that, in the ways that we consciously construct pictures, you can’t help but know that it’s a picture. When you look at it, you go, ‘Oh, this is a photograph.’ You never look at it and go, ‘This was a real moment.’ The picture is entirely self-referential.

AB – And I think that this shift - from reportage into a more studied, distanced, slower process - has been incredibly important to contemporary documentary photography. This approach is quite an entrenched way of working now. From Paul Seawright, to Paul Graham and so on, people are making political work that is distanced. It’s not about the marketplace anymore. It’s about intelligence, and using photography in an intelligent way.

OC – We did this talk at Foto8 the other day about Fig., and members of the audience asked us, ‘What is this going to tell us about the world? How’s this going to change the situation in Darfur?’ In that Foto8 environment, photojournalism is a movement for political change and social change. But I think that one of our concerns - apart from specific issues that we’ve addressed in the work - is about photography itself, and making viewers more aware of the ways in which photography works; the ways in which it functions.

AS – I’ve met a lot of students and young photographers who are extremely passionate about documentary photography, but who quickly become disheartened by it, in the sense that they don’t know how to survive doing it. They might understand its importance in the past, but they see no future in it. Yet you seem to have found a way to pursue your own documentary practice in the twenty-first century, and to still be remarkably successful. What’s the secret?

AB – Well, we teach at LCC on the MA in Photojournalism and Documentary Photography, and every year there’s astounding stuff that comes out, because, in the most naïve sense, photography is just a tool to allow you to be curious. And if you are curious, you’re going to come back with amazing stuff.

OC – Yeah, but how to survive is another question.

AB – But I think that now is the most interesting time for documentary photography. Rather than feeling like it’s in its demise, now is a time of real re-birth, in that you need to be more intelligent and more informed. It’s not just about having big balls anymore; you know what I mean? It’s actually about thinking. The art/documentary crossover has added an important element into the field as well, in that it’s not just about putting pictures on the wall anymore. For centuries the art world has been thinking about aesthetic rules, and the rules of engagement and so on. So it has also become about, ‘How do we apply these rules to documentary?’ There’s a lot more studying to be done on the part of the photographer, rather than just looking at the history of documentary photography. And that’s a real challenge. Whatever the case may be, there’s a real movement happening now, and it’s opening up; everybody’s allowed in. It’s really happening!

SEESAW MAGAZINE: "Fig. - A Conversation with Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin ", by Aaron Schuman

Copyright © Aaron Schuman / SeeSaw Productions, 2008. All Rights

Reserved.

This site and all of its contents may not be reproduced, in whole or

in part, in any form, without the written permission

of Aaron Schuman, and other additional artists involved in the production

of specific works exhibited on this site.